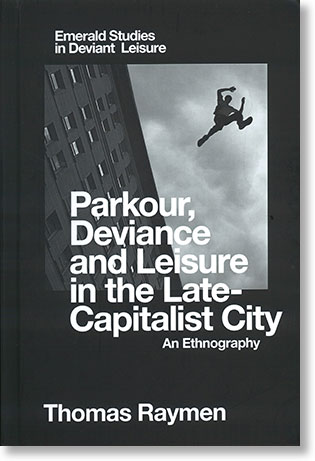

Parkour, Deviance and Leisure in the Late-Capitalist City: An Ethnography

By: Thomas Raymen

Bingley: Emerald 3019 (Emerald Studies in Deviant Leisure)

ISBN 978-1-78743-812-5

Thomas Raymen challenges us to consider how consumer capitalism sits at the heart of even our most transgressive counter-cultural sports and urban leisure activities. The objective of his book is to provide insight into the spatial dynamics of parkour’s practice in the city, but also into the role of parkour in the wider lives of traceurs (parkour athletes) to explain the complex position it holds at the nexus between spatially illegitimate ‘deviance’ and ‘legitimate’ commodified leisure. Raymen asks why parkour is excluded from urban spaces despite conforming to consumer-capitalist commodification through the development of consumer goods, such as fee-paying parkour air-gyms, use in advertising campaigns, television programmes, films, and associated merchandise. The volume makes an important contribution to criminology and leisure to trouble the widely held perception that leisure is good (Rojek, 2010). Raymen brings into view how harm is hidden in the things we seek and love the most in our contemporary consumer leisure cultures.

Through an Ultra-Realist lens founded in transcendentalism and Lacanian philosophy, Raymen theorises how individuals, even though they engage in seemingly transgressive behaviours, lack autonomy and the ability to resist hegemonic oppression. Taking a broad perspective, he shows how contemporary life is embedded in neoliberal consumer capitalism, which places primacy upon identity, entrepreneurialism, risk-taking and ‘cool individualism’. Individualism drives the desire to meet an unattainable ideal (in this case the heroic, brave and strong athlete) that sits at the heart of consumerism, represented through media, from fashion, films to social media, and that leads to a sense of lack and dissatisfaction producing significant emotional labour. Moreover, Raymen challenges the assumption that parkour is a form of political dissent, ‘rebellion’ or anti-capitalist ‘resistance’ popularised within academia and popular culture but is in fact a form of hyper-conformity’ (Chapter 3). This is illustrated by the traceur’s emphatic denial that parkour is a form of social-resistance as well as their entrepreneurial activity that commodifies leisure into gig-work.

The precariousness of post-industrial labour markets and the blurring of work and leisure provide a broad angle for a critical discussion about parkour.

To operationalise theory, Raymen undertook longitudinal ethnographic research in the post-industrial city of Newcastle, United Kingdom, that enabled him to ‘feel’ parkour in an embodied sense as a co-participant living and breathing the life of a traceur. This also enabled him to observe the research participants’ interactions with spaces and people within and those outside of the sport, revealing sensory spatial dynamics as well as spoken lines of enquiry that otherwise would not have emerged. Importantly, by embodying parkour through experiencing the flows of the city, Raymen identifies three key factors: firstly, the tacit dimensions of negotiating sensations of spatial legitimacy and illegitimacy, through performing in physical urban spaces. Raymen exposes how inequality and exclusion are the product of the shift from municipal socialism to municipal capitalism and the transition from democratic municipal governance to pursuing consumer markets. He explores how the processes of regenerating deindustrialising cities into commercial spaces of consumption to make cities economically viable lead to privatisation and securitisation of urban space (Zukin, 1995). Furthermore, capitalism’s use of culture displaces it through the visual display of the city to create a ‘wider symbolic economy’, which provides the multi-sensory spatial ambience conducive to consumption (Chapter 5). Maintaining the experiential atmosphere of space itself is imperative to the city’s economic success, anything that deviates or threatens it is excluded. This was illustrated by traceurs constantly being moved on by security guards from ‘public’ urban spaces even though they were not breaking any formal laws.

Secondly, the role of living the parkour lifestyle is contextualised through exploring the pressures and realities of the lived experience of twenty-first-century capitalism that fixes young people in precarious working conditions in the service economy. The precarity of working life meant that it was hard to make the transition into adulthood, thus infantilising the traceurs because they were unable to secure a living wage and move from the familial home. Raymen points out the contradictory nature of the traceurs’ lives, showing how parkour was originally a form of childish urban-play, that has been ‘adultified’, increasingly professionalised, and commodified – in contrast to the infantilisation of ‘work’ and adulthood that demonstrates the existential insecurity of hyper-exploitative labour markets and the kind of emotional labour young people experience. As Raymen argues, this is a socio-historic moment revealing modern society’s obsession with youth and its socio-economic value.

Thirdly, this led to nuanced understandings of how parkour is a crucial form of identity work that helped to negate sensations of hopelessness and achieve a sense of purpose and wellbeing. Paradoxically, traceurs become prosumers by commodifying parkour practices, whereby leisure becomes work-like in what Stebbins (2007) conceptualised as ‘serious leisure’. By embedding the entrepreneurial spirit of capitalism within the practice of parkour, the traceurs are also offered liberalism’s fabled rewards of autonomy and ‘freedom’ (Chapter 4). The precariousness of post-industrial labour markets and the blurring of work and leisure provide a broad angle for a critical discussion about parkour. Raymen argues that this wider context has been neglected, but it is critical for understanding the attraction to parkour within the global and structural context of socio-economic change. This is contrasted with the spatial realm of parkour that Raymen acknowledges is far more complex by offering authentic, therapeutic and ‘Real’ experiences for the participants. Yet, by drawing on non-representational theory Raymen shows how traceurs embody the physical materiality of the city as an affective space of consumption through their enjoyment of creating images and videos in off-limits spaces; images and representations that would latterly be commodified for others’ consumption.

Thoughtfully weaving a breadth of theory with rich ethnographic research, the book offers a comprehensive analysis for academics and students across the social sciences of the harm leisure produces. Raymen works to answer the questions concerning the paradoxical contradictions of parkour’s position at the nexus between ‘deviance’ and ‘leisure’, asking why this group of people who were actively excluded from urban spaces due to capitalism’s hegemonic control of central city areas, perpetuate and participate in the economic system that marginalises them (Chapter 4). However, it is acknowledged that further work is to be done to explore how hyper-consumption, leisure and gender intersect and how masculinities shape urban spaces of leisure and harm. The book offers insight into the complexity of the integrated relationships between deviance, conformity and the transgression of spatial rules in late capitalist cities and consumer culture.

Copyright © Jenny Hall 2022

Leave a comment